Hey blog followers!

My name is Megan and I am a summer Wildlife Conservation Intern here at  Piedmont Wildlife Center. I am a returning intern from last summer and am extremely happy to be back! Since I have a job at Sears in Wilmington, I only intern Monday through Wednesday. My main tasks here are to care for the education animals which include feeding, socializing, and cleaning up after them. But along with the animal care, I also take part in the Box turtle study we are conducting in Leigh Farm Park, handling our educational birds of prey, helping to construct new raptor cages, and odd jobs around the center that need tending to. I am going to be posting regular blog entries in which I will talk about many different things. I want to share with you what goes on at PWC so you can get an idea of what it’s like to spend the day at Leigh Farm Park. No day is the ever same and nothing is ever predictable and I hope you find my posts as interesting as I find it to work here.

Piedmont Wildlife Center. I am a returning intern from last summer and am extremely happy to be back! Since I have a job at Sears in Wilmington, I only intern Monday through Wednesday. My main tasks here are to care for the education animals which include feeding, socializing, and cleaning up after them. But along with the animal care, I also take part in the Box turtle study we are conducting in Leigh Farm Park, handling our educational birds of prey, helping to construct new raptor cages, and odd jobs around the center that need tending to. I am going to be posting regular blog entries in which I will talk about many different things. I want to share with you what goes on at PWC so you can get an idea of what it’s like to spend the day at Leigh Farm Park. No day is the ever same and nothing is ever predictable and I hope you find my posts as interesting as I find it to work here.

~-~

My first post (today’s post) is an entry that I had up on our blog from last summer. Our blog received a makeover and in the transfer of blogs, my post was lost. I still believe this post explains a great deal about how our box turtle survey is run, why it is run, and what we can learn from it so I will be posting it for a second time.

The Turtle Survey!

Leigh Farm Park, where PWC is located, has a substantial population of Eastern Box Turtles. As North Carolina’s state reptile, these native turtles are an integral part of North Carolina’s natural ecosystem. Without them, the delicate balance of flora and fauna would surely suffer. It is thought that human impacts are affecting our wild Eastern Box Turtle populations. What we don’t know is exactly how much a decline in the box turtle population would impact our natural world. By acquiring box turtles for research and returning them to the wild, we can gain a better understanding of the role these scaly critters play.

Leigh Farm Park, where PWC is located, has a substantial population of Eastern Box Turtles. As North Carolina’s state reptile, these native turtles are an integral part of North Carolina’s natural ecosystem. Without them, the delicate balance of flora and fauna would surely suffer. It is thought that human impacts are affecting our wild Eastern Box Turtle populations. What we don’t know is exactly how much a decline in the box turtle population would impact our natural world. By acquiring box turtles for research and returning them to the wild, we can gain a better understanding of the role these scaly critters play.

When any of us (including the campers) discover a box turtle, we bring them back to the cabin and record a bunch of information about them and then release them to exactly where we found them. This is important because box turtles maintain a territory of their own inside which they know where all of the resources necessary to them are located. These resources include the food, water, and shelter they need to survive. A displaced box turtle would most likely spend the remainder of its life trying to locate its old home. When we find a box turtle, this is what we do:

- Determine the conditions of where the turtle was found including air temperature, sky index, time of last rain, type of habitat the turtle was found in, how it was found, and the coordinates of the turtle at the time of capture.

- Acquire the box turtle’s weight and measure the shell (the upper carapace and lower plastron) at certain places

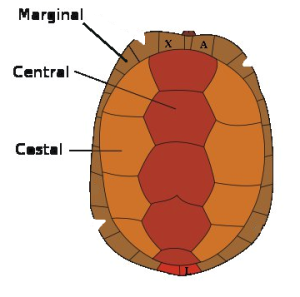

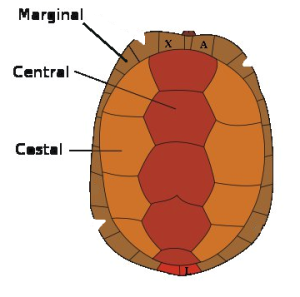

Those distinct sections of the turtles shell that look like patches on a soccer ball are each called scutes. The central scutes run down the back where the spine is located and the costal scutes are the sections on either side of the central scutes. The outer ring of scutes is called the marginal scutes. By counting the annuli on the central or costal scutes, we can get a rough estimate of the age of the turtle. The annuli are the rings found inside each scute that, much like a tree’s rings, can be counted as one year per ring.

Those distinct sections of the turtles shell that look like patches on a soccer ball are each called scutes. The central scutes run down the back where the spine is located and the costal scutes are the sections on either side of the central scutes. The outer ring of scutes is called the marginal scutes. By counting the annuli on the central or costal scutes, we can get a rough estimate of the age of the turtle. The annuli are the rings found inside each scute that, much like a tree’s rings, can be counted as one year per ring.- Determine the gender to the best of our ability of the box turtle using 5 physical characteristics that differ in males and females (I will list them a bit later.)

- Take a few clippings of the nails of the turtle that we place in a vial of fluid to be sent to a lab for DNA testing

- And, finally, we use a method of identification that allows us to identify the turtle if we were to recapture the same turtle which I will now explain: Remember scutes? Now we’re going to talk about the marginal scutes. The tiny scute right behind the turtle’s head is not counted in this process. When looking down at the turtle shell with the bum facing you, the scutes are labeled with letters of the alphabet, starting with “A” and going clockwise. Between scutes “L” and “M” is the tail of the turtle and if you continue to label them all the way back up to the head, the last scute before you get back to the central scute, assuming the turtle has all of its scutes, should be named scute “X”. Now, we have a list of 3 letter codes that we can use to name each turtle. So, let’s say we decided to name the turtle “ABC”. We would take a file and shave a shallow triangular notch in the center of scute “A”, scute “B”, and scute “C”. That way, if we catch the turtle again, we can see that the notches are in the middle of those scutes and know that this is turtle “ABC” that we, say, caught last summer. Turtle shells are much like our nails so filing the notch doesn’t hurt them at all and is completely noninvasive to the lifestyle of the turtle. We never file down scutes D-G and scutes R-U. These scutes, termed the bridge marginal scutes, contain vascular connections between the carapace and the plastron of the turtle. Filing these scutes may harm the turtle so these scutes are never used in naming.

Activity!: I’m going to post a picture of a turtle shell at the bottom of this post and I want you to tell me the name of the turtle based on our naming system! If you get it right, you get the satisfaction of knowing that you’re on your way to being a citizen scientist! Good for you!

The 5 physical differences in male and female box turtles!

A) The eyes: Females will have darker colored eyes compared to the male. Females can have dark brown to pale orange or dark red eyes while males will generally have bright orange, light brown, or yellow eyes.

B) The head and legs: Box turtles have brown scaly skin with yellow or orange accents. The same goes for the shell. Males have much brighter, more pronounced yellow accents on their bodies and shells than females who will be a duller, pale yellow or orange. The way I like to think of it is that male birds generally have brighter colors than female birds. Same goes for turtles.

Male (left) and female (right)

C) The shell: Since females have to store eggs under that domed carapace, they tend to have a higher shell than male turtles. This can be hard to tell unless you have a male and a female to compare to one another. Also, the marginal scutes near the rump of male box turtles flare outward while females do not.

D) The plastron: The plastron is the bottom plate on the tummy of the turtle. Males will have a concave section in their plastron that will assist them in staying on the female during mating.

E) The tail: Females have small, short tails while males have longer, fatter tails.

Matching just one of these characteristics isn’t enough to reliably determine the turtle’s gender. For instance, females can also sometimes have a slightly concave plastron or show distinctly bright eye color but still be a female. The only way to be certain is blood testing but what we do is see which gender gets the most matches.

As always, thanks guys! Take care!

Here's your educational activity! What's his name? Leave a comment and let me know!

One of the biggest struggles we as Wildlife Conservation Interns have is getting the chickens to go in their coop in the evening. They might go in the coop by their own choosing if it became dark but we usually leave when there is still daylight so the chickens are reluctant to go in the coop. One of the things I try to do is to teach them to come to me when I crouch down and call for them. I also continuously say the word “coop” when I want them to go in the coop. They are making great progress but a little bit of motivation in the form of a treat is always a help.

One of the biggest struggles we as Wildlife Conservation Interns have is getting the chickens to go in their coop in the evening. They might go in the coop by their own choosing if it became dark but we usually leave when there is still daylight so the chickens are reluctant to go in the coop. One of the things I try to do is to teach them to come to me when I crouch down and call for them. I also continuously say the word “coop” when I want them to go in the coop. They are making great progress but a little bit of motivation in the form of a treat is always a help.